The Supreme Court‘s decision last month in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overturned 1973’s Roe v. Wade and its 1992 successor, Planned Parenthood v. Casey, represents a historic moment in American history. For pro-life activists and conservative legal movement activists, the Dobbs case is nothing short of epochal. The constitutional order has been vindicated and a grievous moral stain has been eradicated; millions upon millions of unborn children will be spared an untimely demise in utero. The feeling is both surreal and euphoric: The modern conservative legal movement has finally been vindicated on its marquee issue.

But Dobbs is not the end of the pro-life struggle. True, it represents the crowning achievement for a generation of conservative lawyers who built a movement to countermand mid-century judicial excess and, above all, overturn Roe. But younger conservative lawyers, who gravitate toward a more substantive approach to originalism, see clearly the overarching moral imperative of abortion abolitionism. As Abraham Lincoln argued in his 1854 Peoria speech, the relevant moral and legal question in the antebellum slavery debate was whether a black American “is not or is a man”; so, too, is the relevant moral and legal question in the abortion debate whether the unborn child is not or is a natural person.

We know the biological answer to that question: Yes. Fortunately, a proper interpretation of the Constitution’s 14th Amendment, with its sweeping language securing the “equal protection of the laws” for “any person,” codifies that intuition into our national legal charter. Because the unborn child is a natural legal person—according to venerable authorities like William Blackstone and an unbroken chain of state high court cases leading up to the 14th Amendment’s ratification in 1868—a homicide statute that protects born persons but not unborn persons necessarily violates the Constitution’s equal protection guarantee.

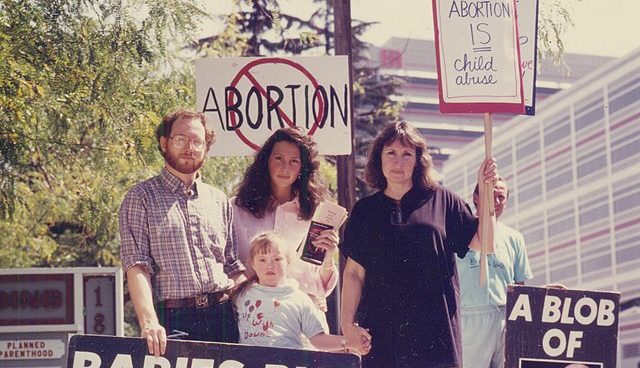

Justice Samuel Alito‘s majority opinion in Dobbs actually hints at this understanding of 14th Amendment personhood. Dobbs “sharply distinguishe[d]” other cases on which Roe and Casey relied based on the reality that “abortion destroys what those decisions call ‘potential life’ and what the law at issue in this case regards as the life of an ‘unborn human being.'” In other words, Dobbs rejected Planned Parenthood’s noxious “clump of cells” disinformation and candidly acknowledged the moral salience of the unborn child.

It is thus not a far leap from Dobbs to constitutional personhood. The hurdle is not one of moral, biological, or constitutional truth, but rather one of fortitude and sheer willpower. All relevant constitutional actors must flex their muscles to help us reach the promised land of an abortion-free America.

First, Congress should “enforce, by appropriate legislation,” this proper understanding of the Equal Protection Clause. Congress is the institution primarily responsible for securing the Amendment’s guarantees.

Second, the judiciary should, in future cases where the issue is squarely presented, rule on the side of natural legal personhood for the most vulnerable and defenseless among us. Lower federal court judges should heed Dobbs‘ emphasis on the state’s interest in protecting unborn human life, based on what one of us has described as a “common-good maximization principle” for lower-court judging: When in doubt, “defer to the substantive common good and background principles of our common-law inheritance.” Here, that militates in favor of 14th Amendment personhood.

Third, the next pro-life president must independently act to properly interpret the Equal Protection Clause and impose that interpretation throughout the Executive branch. This does not substitute for sweeping congressional or judicial action, but it would make for dramatic incremental progress.

Finally, pro-life activists can advance the broader cause of constitutional personhood at the state level. Pro-lifers must work, especially after Dobbs, to pass laws and state constitutional amendments defining legal personhood as beginning at conception. Such an incremental, state-by-state shift in the legal landscape could galvanize momentum toward a federal abortion ban—whether it comes from Congress, from the Supreme Court, or via constitutional amendment.

In an 1858 address, Abraham Lincoln warned that “a house divided against itself, cannot stand.” A patchwork federalism approach—what Stephen Douglas, Lincoln’s frequent 1858 debate opponent, appealed to as “popular sovereignty”—to such a profound moral question as abortion is unsustainable. The United States could not endure “permanently half slave and half free.” So too can we not endure a regime under which vulnerable unborn children could be legally protected in Texas, but not in California.

Thank goodness for Dobbs. But for our generation of abortion abolitionists, the fight is not over until every unborn child in America is protected by love and by law.

This article originally appeared on Newsweek and can be read here.