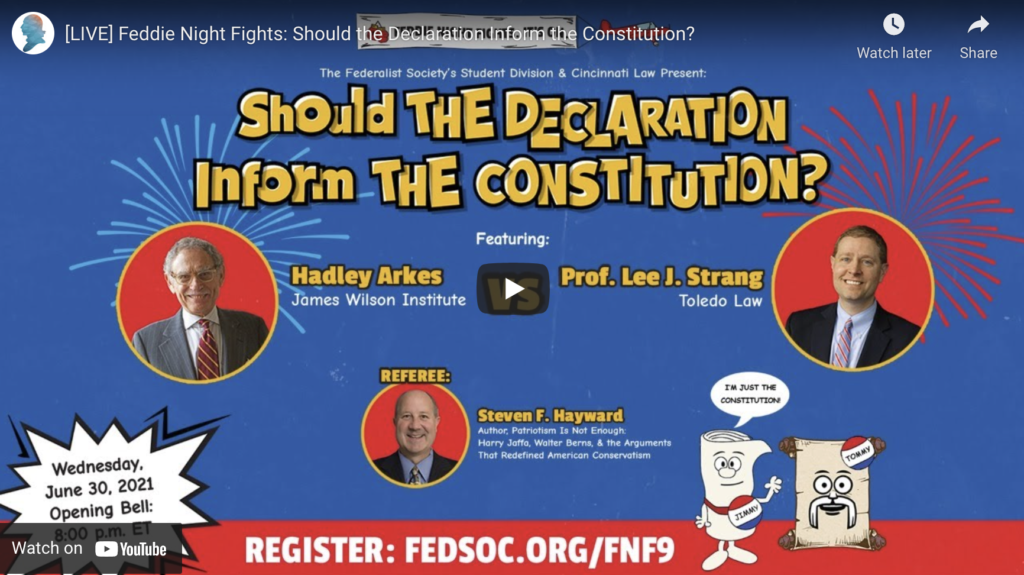

In a recent debate with Professor Lee Strang, Professor Arkes argued that the Declaration of Independence is the interpretive key to the Constitution (you can find both the video and the transcript of the lively exchange on the blog). While I think Arkes had the better of the debate, he left implied a few premises that should be forthrightly declared.

To begin with, what do we mean by using the Declaration as the interpretive key to the Constitution? The Declaration sets forth a series of First Principles of government and lawfulness. The Constitution must be read against the backdrop of those principles. After all, the Declaration—not the Constitution—created the polity that enacted the Constitution (and the Articles of Confederation that preceded it). The Declaration is the true “constitution” of the United States, insofar as it is the constitutive document of the United States. Thus, what the Declaration constituted, the Constitution cannot be read to undermine.[1]

The foundation of government, according to the Declaration, is the nature of human beings: all men are created equal, and are endowed with inalienable rights. Those rights come from man’s Creator—they belong to each of us as part of the very nature of a human being—and are not granted by the government, the will of other men, or some force of positive law.

The fundamentally equal, rights-bearing nature of human beings creates two important boundaries for government. First, the government’s duty is to secure those inalienable rights that all men possess by nature. It can neither grant nor rescind them, since they derive from the Creator and the very nature of human beings. Second, a good government—a “just government”—can rule only by the consent of the governed. Why? Because all men are equal, so one man (or group of men) cannot justly claim to rule over his equals without their consent. If instead some humans were simply ordained by nature to rule others, then not all humans are equal. Put another way: human beings are not made equal by the force of positive law; their prior equality is what makes the positive law possible in the first place.

The natural law principles of the Declaration—equality of all mankind and government by consent—have important implications for the way we read the Constitution when confronted with vague emanations from penumbras. There are some evils—deep violations of natural law—that the positive law can create and sustain. Chattel slavery was of course America’s preeminent violation of natural law, and the fountainhead of ills we still deal with today. And much ink has been spilled stating the (quite correct) proposition that chattel slavery was incompatible with the principles of the Declaration, precisely because slavery denies the fundamental equality of slave and slaveholder, and by definition it involves the rule without consent.

But the old practice of slavery and its place in the Constitution does not undermine the role of natural law. It is instead the proverbial exception that makes the rule clearer. First, the Constitution’s slavery provisions (which themselves take pains not to use the word) make clear that some things can exist only as explicit creatures of the positive law. The right to worship God according to one’s conscience is a right implicit in the order and nature of human beings. That right would be evident—self-evident, even—regardless of whether the Constitution had a Free Exercise clause. But the right to own another human being is not that kind of right. One could not find a right to make slaves of fellow human beings in the implications, emanations, or penumbras of the Constitution; it must be there explicitly or not at all. And it follows that where the positive law creates or sustains an evil, the law must be read narrowly. The Rule of Law may command that you abide by even misguided positive law. But evil has no right to deference, emanations, or penumbras.

In Washington v. Glucksberg, where plaintiffs tried to find a Due Process right to physician-assisted suicide, Chief Justice Rehnquist observed that Due Process protects only those rights “deeply rooted in our nation’s history” and “implicit in the concept of ordered liberty.” Which is to say that to dragoon another into helping you kill yourself is a right that can only exist—if it may exist at all—as a creature of the positive law. It cannot be willed into existence from the shadows of Due Process.

While the Declaration’s fundamental moral principles have largely been sidelined in “modern” jurisprudence, truth is a stubborn thing. As the late Chief Justice showed, the tools of the natural law are with us still, as long as jurists have the courage to wield them.

[1] Here I do take issue with one of Professor Strang’s points. I believe the Declaration’s Bill of Complaints is in fact an interpretive key to the Constitution’s explicit provisions. Nearly all of the complaints against King George (with the possible exception of the complaint about the Quebec Act) find some remedy in either the Constitution’s structural articles or the Bill of Rights.

It makes little sense to argue that the Declaration outlived its usefulness as soon as independence was accomplished. For the Framers could not pen the Declaration and then constitute a government that is by nature and operation guilty of the same offenses and abuses. After all, the Declaration itself says that such a government would be unworthy of allegiance, and it would be the right and duty of the People to cast it off and set up (yet another) new one. More to the point, we would no doubt think it wrongful for George Washington to serve as Commander-in-Chief against what he saw as a tyrannical government, and then make himself head of an equally tyrannical government.