We know that the free speech clause of the First Amendment protects us from government censorship. But suppose someone raises the question, “What’s the point of freedom of speech?” To provide an answer, you cannot simply appeal to the Constitution, since the questioner is asking you to justify what is in the Constitution. You must enter the realm of philosophical argument and offer reasons why one ought to believe that freedom of speech is good. To employ a mundane illustration, it’s one thing to say the speed limit on the interstate is 75 mph, it is quite another to ask whether 75 mph ought to be the speed limit.

Suppose in answering the free speech question you appeal to a variety of reasons including the goodness of the pursuit of truth in politics, science, and letters. You argue that the truth in these matters is so important, and so vital to the common good, that it is better to risk error—the occasional exercise of mistaken or even hateful speech—than to allow government censorship and to risk the loss of truth. But the persuasiveness of this answer ultimately depends on what your audience already believes about what counts as goodness. For imagine you live in a society in which the purveyors of elite opinion are convinced that there’s no such thing as “truth.” What then do you say?

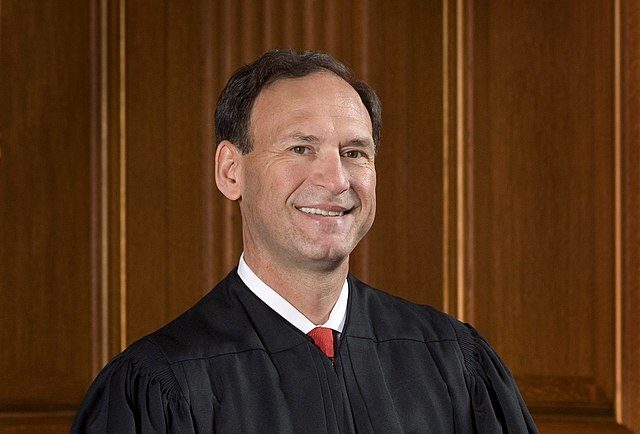

Speaking in Rome last month, Justice Samuel Alito argued that we may be approaching such a scenario when it comes to the freedom of religion. In his July 21 keynote address at Notre Dame Law School’s Religious Liberty Summit, Alito warned his audience that “we can’t lightly assume that the religious liberty enjoyed today in the United States, in Europe, and in many other places will endure.” He noted that many legal academics who write on religion no longer believe that it merits special protection, for they maintain that “a liberal society…. should be value neutral, and therefore it should treat religion just like any other passionate personal attachment,” such as “rooting for a favorite sports team, pursuing a hobby, or following a popular artist or group.”Even though a variety of legal instruments—including the U.S. Constitution and several international declarations—single out religion for special protection, that is no guarantee that judges could not shrink the scope of religious liberty.

Although he does not mention them by name, Alito is referring to several important academic books and articles, published over the past two decades, that have such titles as Why Tolerate Religion? and What if Religion Is Not Special?, and that include comments like, “our theory depends upon the idea that the state must not discriminate between religious conviction and comparably serious secular convictions” and “religious belief is a culpable form of unwarranted belief.”

Even though a variety of legal instruments—including the U.S. Constitution and several international declarations—single out religion for special protection, that is no guarantee that judges could not shrink the scope of religious liberty. As Alito noted in his speech, religious liberty is not absolute. Like every other right, it can be cabined by considerations like public safety, order, and health. This is why laws against child sacrifice, even if motivated by sincere religious belief, do not violate the First Amendment.

But Alito is not warning us about the state reining in such extreme religious practices. What concerns Alito is what could happen in a society in which religious practice has significantly declined, a society in which many citizens no longer see the point of religion, and thus try to find some secular analog (like devotion to a sports team or a hobby) to help them better understand their neighbors’ faith. In such a society, it will seem irrational to its many citizens for the state to accommodate church attendance during a pandemic while it allows what everyone agrees are essential services.

A judge, armed with the legal caveats of public safety, order, and health, and who, like many of his compatriots, does not see the point or reasonableness of religion, will likely think of a church’s request for a special accommodation as no different than one requested by the Optimist’s Club or the Culinary Union. If religious liberty is not about something integral to human existence—if it’s not ultimately about one’s rightly ordered relationship to the transcendent source of being (God)—then churches are politically indistinguishable from other civic groups.

“When the state signs on to protect religious liberty,” Alito noted, “it necessarily signs on to a particular conception of what it means to be human.” Thus, if a religious association is, from the perspective of the government, no different than any other voluntary association, then whatever the state declares is in the interest of public safety, order, and health will always trump religious liberty.

That is a warning we all need to hear.

This essay was originally published at WORLD and republished with permission.